Years ago, I moved from one state to another. Mumbling under my breath about the pressure of quickly unpacking, a ceramic bowl slipped out of my hand and fell to the floor. I stared at it in upset, the bowl had broken cleanly into three pieces. I quickly scooped the pieces into the trash, and soon afterwards, I replaced it with a new bowl. That is part of the modern culture, that it’s the reason for everything from our piles of trash to our relationships, to our work, to governing our society. When something breaks, we throw it away.

My family and I had the good fortune of living for a few years in Japan during the years following the war. I found the people to be, as a whole, more gracious and courteous to one another than I was accustomed to. Their homes, stores, and way of life was simpler and organized. What little they had, they treated with respect. And when they broke something, they repaired it instead of simply replacing it as we do in our society.

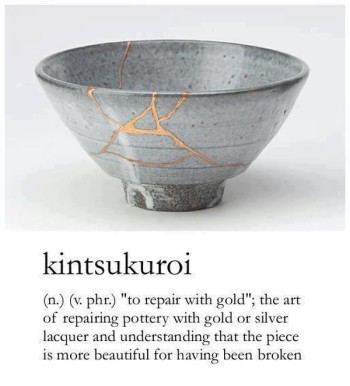

In ancient Japan, when a ceramic bowl broke, they fixed it. Legend has it that a Japanese shogun was unimpressed with the repair done on a Chinese bowl he had sent to be fixed, so he hired some Japanese craftsmen to find a more beautiful method of mending ceramics. They developed a technique called kintsukuroi, in which the broken pottery is literally mended with gold dust. Rather than trying to hide the flaws in the broken  ceramics, they would highlight them in gold, baring the cracks and scars and adopting them as a part of the ceramic.

ceramics, they would highlight them in gold, baring the cracks and scars and adopting them as a part of the ceramic.

The technique became so popular that people may have even begun intentionally smashing bowls and plates in order to have them repaired. The ceramics mended with kintsugi actually became more valuable than they had been before they were broken.

It was considered more beautiful because it was broken. Kintsukuroi craftsmen had to be very skilled and the most celebrated among them were those who could repair even the most destroyed pieces of pottery.

In our culture of throwing-away, our government, churches, medical system, legal system, and communities are filled with broken people hiding their scars in shame. Our current culture is not always a safe place to show our ragged edges and search for healing, so we metaphorically superglue ourselves back together and hope no one notices the growing cracks.

Now, I recognize that not all things that are “broken” should be fixed. There are times things need to stay broken and discarded. Sometimes they are allowed to be “broken”, because if something is not changed our life will not be what it should or could be. But, we say we believe in a God who is strong, who can heal our weakness, who makes us new creations, who is a God of repair and restoration and redemption. What kind of a witness do we give if we say we believe in a God of healing but will not learn how to heal rather than discard.

The God we revere has provided a process, a way to mend our broken pieces back together with something more beautiful and precious than gold. This process should be acknowledged and we need to better learn to fix broken things, we need to bare our scars in our art and in our lives.

Because the kintsugi craftsmen had another purpose in their craft. As they repaired ceramics from all over the world, Chinese bowls and Korean plates, as they mended the cracks with precious gold, the pottery was no longer considered Chinese or Korean. Once something was mended with kintsugi, it was forever considered Japanese. In the same way, we should recognize and implement truths and methods to fix whatever is broken in our lives, and provide a way to make life more beautiful in the process. If it were not so, what is forgiveness about?

The repairman had left his mark on the pottery so distinctly that it was no longer recognized by where it had come from, but by who had repaired it. We need to give credit to those who take the time and effort to make life better in some way.